Lifespans and Timescales: Designing for Resilience, Relevance, and Regeneration

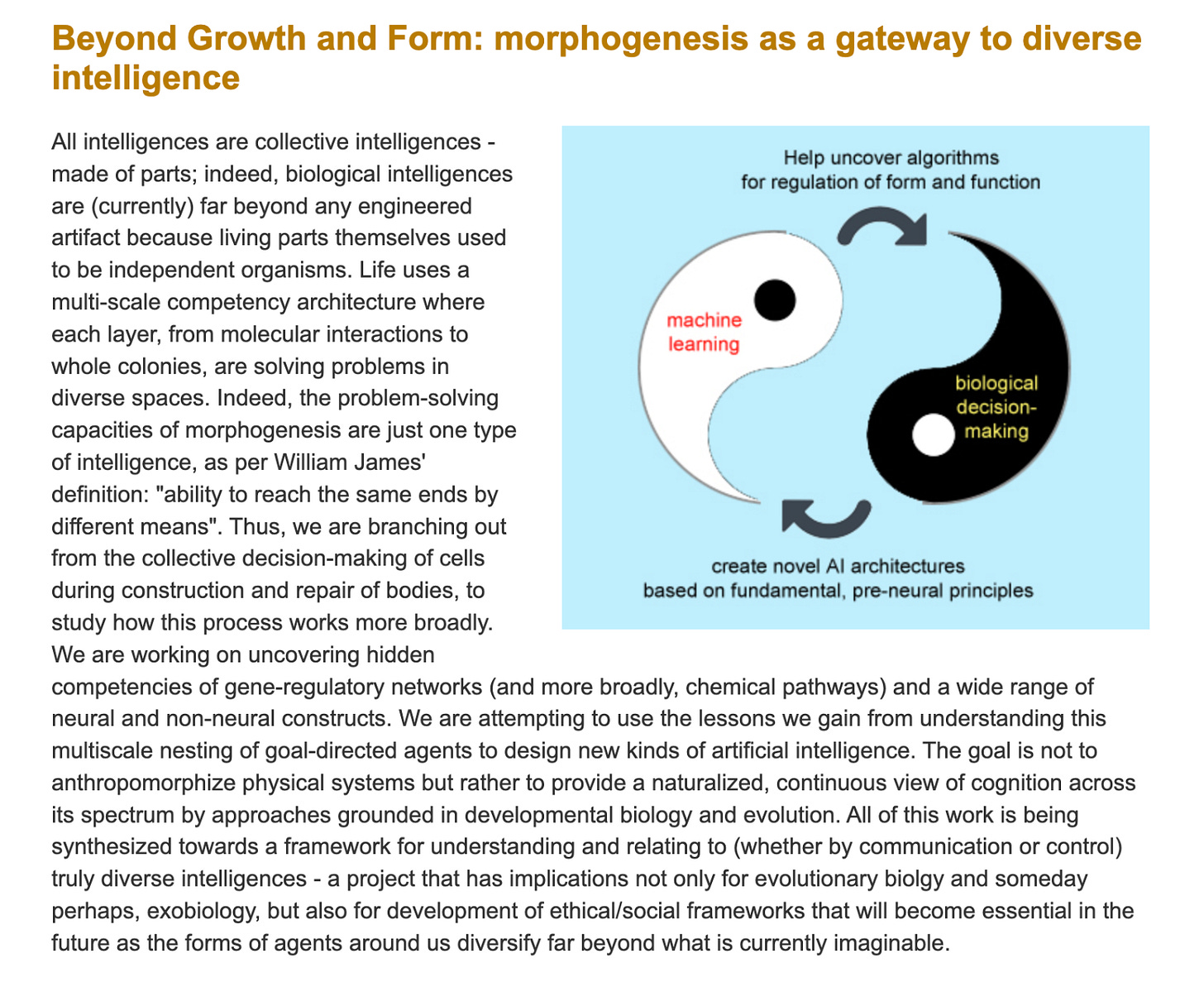

Equipping the Longevity Generation with Destination Discernment and the Architecture of Enduring Flourishing

Most conversations about longevity begin in the lab—or at least, they pretend to. We hear talk of lifespan extension, senescence, gene therapies, epigenetic clocks. But these speculative narratives often race ahead of the research itself. The public discourse paints a picture of boundless possibility, while the actual science remains cautious, fragmented, and unevenly applied.

Longevity R&D aims to stretch the timeline. But flourishing and progress depends on what we do with the added space. A longer life is not necessarily a better life—especially if our systems, institutions, and social contracts remain built for shorter, more linear, and more fragmented timelines.

We are entering an era where biological breakthroughs, artificial intelligence, and social upheaval are converging. The future of health will not only be determined by what we can do to the body, but by what we know how to do with each other—how we learn, mentor, coordinate, build, adapt, and sustain direction in an age where everything is speeding up and breaking down.

If we are to meet this moment, we must expand our definition of longevity. We need more than cellular rejuvenation—we need cognitive durability, institutional relevance, and intergenerational regeneration. We need a culture and infrastructure that supports long-term flourishing: of minds, missions, and communities.

This essay is a call to reimagine longevity not just as a biological feat, but as a design challenge. It’s about building the scaffolding—personal, interpersonal, and systemic—that enables us to remain adaptive, coherent, and humane in a 100-year world. Drawing on lessons from healthcare and health technology, mentorship ecosystems, organizational strategy, and interdisciplinary innovation, I suggest that the most important longevity technologies might not come from a petri dish—but from how we shape people, programs, and paradigms for endurance, not just expansion.

Here, I explore what it means to build not just longer lives, but long-term coherence: in our systems, selves, and societies. I argue that supporting what I call the Longevity Generation—those who will live through and shape this century’s transformation—requires a new kind of compass. We need not just direction, but what I call Destination Discernment: the ability to chart meaningful trajectories through complexity; and in this case, development, care, and innovation through social, institutional, and technological complexity—without losing sight of what truly matters.

II. What Longevity Leaves Out

Three Metaphors for Misalignment

A few metaphors and analogy to situate the forthcoming discussion:

Imagine cultivating a rare, long-living plant species—but in soil that’s depleted, in a climate that’s volatile, with no gardeners to tend it. That’s what our current longevity paradigm risks: biological extension in an ecosystem unprepared to sustain it.

In software, an infinite loop is a failure of logic—a process that repeats without progress. We risk the same with longevity if we extend time without redesigning the systems that give it shape, function, and exit conditions.

More time isn’t always a gift—it can be a maze without a map. We’re extending lifespans but not equipping people or institutions with the tools to navigate those added years with clarity, purpose, or coherence.

A Brief Story

A few years ago, I was sitting in a meeting with R&D leads and executives at a healthcare technology company, discussing the roadmap for our next generation of monitoring tools. On paper, we were making progress: better sensors, more robust data pipelines, even early integration with predictive AI systems. But something felt missing. In our push to optimize what we could measure, we had neglected to ask what really matters in the long arc of human health.

Securing buy-in around what should even be considered—or offered—was difficult. There was (and generally is) a persistent tension between what the market was ready to adopt, what human well-being actually required, and what was even close to scalable.

This is a pattern I’ve seen across biotech and innovation spaces: a fixation on the molecular and the mechanical, with little room for the mental, social, and ecological. There are parallels and overlaps with other major philosophical matters as well: the longstanding rift between reductionism and complexity (Fraser & Greenhalgh, 2001; Noble, 2006); and even in a more applied sense, the role of embodiment in cognitive sciences (Varela, Thompson & Rosch, 1991; Shapiro, 2010).

Longevity gets framed as a problem of biology alone—extend the telomeres, slow the senescence, fix the protein folding. Rarely do we ask: What kind of life are we extending? And for whom?

We treat health as a personal variable, but it is deeply shaped by systemic forces—educational opportunity, mentorship access, social scaffolding, narrative framing. I’ve mentored dozens of early-career researchers and technologists through JOPRO, Orthogonal Research and Education Lab, Google Summer of Code, and now From Here to There: Strategy and Mentorship for Innovators and Data x Direction, and what I see most often isn’t a lack of intellect or drive—it’s burnout, decision fatigue, disorientation. Not just biological stress, but strategic and spiritual depletion. These too are longevity challenges. Research on burnout and stress (Peters, McEwen, & Friston, 2017) and the classic work of Christina Maslach underscore how chronic overload erodes capacity.

If we build medical interventions without parallel social and institutional designs, we risk extending time without meaning. Healthspan isn’t just about vitality metrics—it’s about being able to contribute, connect, and navigate life with coherence. It’s about flourishing in motion, not just surviving in stasis. This broader lens aligns with research on the social determinants of health (Marmot, 2005).

The current paradigm of longevity is siloed and shortsighted. We need a broader lens—one that acknowledges that real longevity is a social and strategic achievement, not just a biological one.

III. Mentorship as Infrastructure

When we think about infrastructure, we usually picture roads, bridges, power grids—the physical systems that hold up our daily lives. But in the context of a longevity-focused society, mentorship and intentional cultivations of intra- and inter-personal skillsets may be one of the most underappreciated forms of infrastructure we have.

Mentorship is not just a nicety or a professional development perk. It is a mechanism of resilience, a means of knowledge transfer, a system for emotional and strategic co-regulation across generations. It provides the social scaffolding that allows individuals and communities to orient themselves toward long-term goals, especially in volatile and uncertain contexts.

Through my various roles, I’ve mentored early-career scientists, technologists, and interdisciplinary thinkers navigating fields that often lack clear roadmaps. What I’ve found is that mentorship done well doesn’t just pass along information—it cultivates discernment, direction, and durability. It helps people manage complexity, interpret failure, and sustain coherence over time.

These are far beyond “soft skills” that offer tertiary levels of enhancement. They are survival traits in a world where timelines stretch, decisions compound, and crises multiply. This is something Douglas Rushkoff explores in Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now—a powerful diagnosis of our cultural breakdown under temporal disorientation. Rushkoff argues that our collective inability to inhabit coherent timelines has created a crisis of meaning, purpose, and continuity. In a longevity context, this insight is critical: as our lifespans extend, so too must our ability to make sense across longer arcs. Mentorship, in this frame, becomes not just career guidance—but narrative restoration.

In biotech, in AI, in health innovation, mentorship and destination discernment —our ability to develop advances in technology to viable destinations— are what connects the speed of technical development with the wisdom required for ethical deployment. Destination discernment—echoes calls from long-term thinkers like Stewart Brand and Roman Krznaric, who remind us that future-fluent action demands tools for anchoring foresight in action, not just prediction. These are, in effect, a public health intervention—one that shapes not just individual careers, but the collective trajectory of fields poised to redefine life itself.

To mentor the longevity generation is to design for systemic continuity. It means building pipelines that don’t just prepare young people to enter today’s institutions—but equip them to adapt, critique, and evolve those institutions for a future we can’t fully predict. It means treating mentoring not as episodic advice, but as a design principle embedded into the DNA of innovation ecosystems.

And it means recognizing that every time we mentor well, we don’t just extend someone’s opportunity—we extend the timeline of what’s possible for all of us.

IV. Cognitive Longevity: Leading Without Burning Out

If biological longevity is about extending the body’s capacity, cognitive longevity is about extending the mind’s. This includes not just preserving memory or preventing burnout, but cultivating the capacity to lead, learn, and make decisions across longer, more complex timelines.

In an era defined by information overload, increasing volatility, and accelerating change, decision-making itself is under threat. Many leaders—whether in science, business, or public service—are stretched thin by fragmentation and fatigue. Cognitive longevity means developing habits, frameworks, and institutional practices that allow people to sustain direction, coherence, and creative agency over decades, not just quarters.

As OpenAI CEO Sam Altman recently noted in a discussion on preparing for the future, beyond learning technical tools, the core traits that will define success are adaptability, resilience, and the ability to discern what others truly value. These “super learnable” skills, as he calls them, are not only crucial for navigating the near-term impacts of AI—they are essential for long-range directionality in a volatile world. In his words: “When AI can kind of do anything… then deciding what to do and what people value is going to be really important.”

Cognitive load theory, originally developed in educational psychology, highlights the importance of working memory and schema development in managing mental complexity. But its lessons are rarely applied to leadership or institutional design. Similarly, the literature on adaptive expertise (Hatano & Inagaki, 1986; Schwartz et al., 2005) shows that expert practitioners don’t just repeat learned solutions—they know when to pivot, adapt, and innovate. This kind of flexible intelligence is precisely what longevity demands.

In my work across health tech & healthcare, innovation ecosystems, and consulting and mentoring at large, I’ve seen how the absence of cognitive sustainability creates cascading failures—good projects stall, good people burn out, and institutional knowledge dissipates. At scale, this becomes an innovation bottleneck.

We need environments that actively support cognitive renewal: sabbatical structures, mentorship webs, reflection loops, and epistemic humility baked into governance. The best organizations invest not only in what people know, but in how they regenerate clarity and discernment over time. Think of this as the organizational equivalent of mitochondrial health.

The stakes are high. In domains like AI, biotech, and public health, short-term thinking can produce irreversible consequences. Developing cognitive longevity is, in this sense, a form of ethical risk management. As the philosopher Norbert Wiener warned in the mid-20th century, our technical power will always outpace our capacity to govern it—unless we deliberately cultivate foresight and responsibility.

To thrive in a 100-year world, we need minds that can think in 100-year arcs. That means leaders who can hold paradox, metabolize uncertainty, and operate with sustained attention in an age of distraction. It also means treating wisdom not as a byproduct of aging, but as a practice we can design for—and a critical input for human flourishing.

V. Living Systems and Institutional Healthspan

If people are living longer, our institutions must learn to do the same—not through stagnation, but through adaptive vitality. Yet most organizations age poorly. They calcify. They forget. They resist renewal. To design for true longevity, we need to treat institutions not as static bureaucracies, but as living systems.

This shift requires a new ontology of organizational life. Just as living organisms metabolize resources, process feedback, and repair themselves, resilient institutions must also sense, learn, adapt, and regenerate. The fields of complexity science and cybernetics offer powerful metaphors here: feedback loops, homeostasis, self-organization, distributed intelligence. These are not buzzwords but rather they’re the operational grammar of long-term relevance.

To design for true longevity, we need to treat institutions not as static bureaucracies, but as living systems.

At Orthogonal Research and in collaborations with DevoWorm (a project under the OpenWorm Foundation), we’ve explored how principles from systems biology and morphogenesis can inform institutional behavior. One insight: aging institutions often lose the ability to integrate novelty without chaos. Like overburdened biological systems, they become inflamed, rigid, and brittle—what in human terms might resemble autoimmune response. What’s more, an ongoing Google Summer of Code project series is about Open Source Sustainability, which specifically addresses the challenges of whether open source projects have an enduring link to the rest of the software economy - or not.

To extend institutional healthspan, we must cultivate "meta-mentorship": not just mentoring individuals, but mentoring the environments and processes that shape how knowledge moves and decisions evolve. This includes modular design, pluralistic governance, and regenerative cadence—space for pause, reflection, and reconfiguration. In our Society Ethics Technology working group, we are exploring how values-forward design and decentralized governance protocols can strengthen epistemic resilience at scale.

This is also where destination discernment reappears—not just as an individual capacity, but as an institutional function. Projects like FrontierMap are designed to scaffold the navigation of complex research terrains, helping teams and organizations discover not only what's emerging, but where it’s actually worth going. In institutional contexts, this means knowing how to sunset, pivot, or evolve responsibly—rather than chasing relevance indefinitely.

Examples exist. The Santa Fe Institute models how intellectual ecosystems can evolve across decades. The Metagov Project explores programmable governance. The Long Now Foundation builds literal and metaphorical infrastructure for multi-century thinking. These aren’t fringe efforts—they’re testbeds for what it means to embed longevity into the DNA of our social systems.

Ultimately, we must stop asking only how long people can live—and start asking what kinds of environments we need to age well together. Institutional healthspan is the invisible architecture behind every meaningful long-term effort. Without it, we extend lifespan into systems too fragile to hold it.

VI. Biotech Needs a Compass

Biotech is often framed as the frontier of human enhancement—the most literal domain of longevity science. From gene editing to neurostimulation, we are rapidly gaining the ability to alter the substrates of life. But the speed of possibility is outpacing our frameworks for meaning. In this space especially, we need a compass, not just a map.

As I’ve written elsewhere, technological trajectories without destination discernment risk becoming expressions of capability rather than contributions to human flourishing. Just because we can doesn’t mean we should—and even when we should, we must still ask: toward what end? And for whom?

The current biotech narrative is missing a critical scaffolding: the moral, narrative, and governance infrastructure needed to guide not only what we build, but how we relate to it. We lack coherent stories of where we are going, or what we want from our tools. Ethical review boards and regulatory frameworks are necessary—but they’re not sufficient. We need cultural architectures of intentionality.

This perspective also resonates with emerging work on diverse forms of intelligence—biological, artificial, or hybrid. As biotechnological capabilities expand, so too does the imperative to rethink agency and ethics. Michael Levin, whose work bridges developmental biology and synthetic morphogenesis, notes that the goal is "to provide a naturalized, continuous view of cognition across its spectrum [...] toward the development of ethical/social frameworks that will become essential in the future as the forms of agents around us diversify far beyond what is currently imaginable."

In other words, the future of biotech won’t just reshape biology—it will demand that we reshape how we conceive of agency, empathy, and responsibility. The ethical frontier is expanding, and our compass must be capable of pointing toward futures that include, rather than marginalize, the full spectrum of sentient and semi-sentient life. This is Destination Discernment at its broadest scale: not just where our tools go, but who we include in the future we’re aiming for.

This is especially urgent in longevity science, where interventions are marketed in terms of personal optimization but enacted within systemic inequity. Scholars have increasingly called attention to how medical access, algorithmic bias, and even definitions of 'health' often reflect privileged norms. Critical disability studies, for example, highlights how mainstream health interventions can erase the needs and insights of neurodivergent, disabled, or chronically ill communities. Researchers in fields like STS (Science and Technology Studies) and feminist technoscience have emphasized the need to center pluralism in our visions of human flourishing. See works such as Alondra Nelson’s "Body and Soul", or the interdisciplinary project AI Now, which addresses social inequities embedded in emerging technology. What values are embedded in a lifespan-oriented society? Who defines vitality? What constitutes a worthy extension of life—and who gets access to it?

To fill these gaps, we need a new generation of transdisciplinary translators—people who can connect the hard tissue of technology to the soft tissue of values, narrative, and social design. This is part of what we aim to model in our JOPRO mentorship and strategy efforts: helping researchers and innovators locate their work within larger arcs of purpose.

It’s also what animates a new wave of organizations like The Roots of Progress and The Cosmos Institute, which attempt to reclaim a positive, human-centered and narrative of technological development, as well as affirming the moral imperative of tending to progress, and establishing the Philosophy to AI Pipeline. The goal isn’t to slow down innovation, but to shape it. Progress is not just acceleration—it’s alignment.

In an age of powerful tools, the ethical frontier is design. And in the longevity era, the compass we need most is not pointing us faster into the future—it’s helping us hold direction as we go.

VII. Vignettes and Personal Examples

Theories are sharpened by proximity to lived experience. Much of what I’ve argued throughout this essay comes not just from reading and reflection, but from being embedded in interdisciplinary, innovation-heavy environments where real people confront real limitations—and try to transcend them.

In my work in the health domain, I sat in cross-functional meetings where machine learning engineers, hardware developers, and clinicians wrestled with trade-offs between feasibility, scalability, and meaning. On one hand, we could build increasingly sophisticated tools for niche patient monitoring and wellbeing; on the other, we had to contend with messy realities: user fatigue, accessibility gaps, technological buy-in, and regulatory uncertainty, just to name a few. I watched how cognitive overload wasn’t just an individual issue—it spread through teams and leadership, subtly shaping what got prioritized and what quietly fell off the roadmap.

Through my various roles, I’ve mentored early-career researchers, mid-level managers, and even advised and consulted with executives—many of them navigating emerging fields like data ethics & responsible AI; updating psychology and neuroscience to incorporate advances in mental health and neurodivergence; developmental biology and other STEM fields meshing with complex systems and metascience. Again and again, I’ve seen how mentorship and destination discernment function not just as guidance but as grounding: stabilizing forces that lets people sustain direction when no clear institutional lane exists. These moments of “holding steady” matter just as much as breakthrough moments. They are the socio-emotional infrastructure of innovation.

Even more personally, I’ve watched people close to me—family, friends, collaborators—grapple with what it means to live a meaningful life under chronic illness, economic precarity, or cultural misrecognition. These aren’t footnotes to the longevity conversation; they’re central. They illuminate the distance between biological extension and systemic support.

This arena of work I’m attempting to demarcate via this essay is, in many ways, an attempt to honor that distance. And to suggest that closing it will take not just progress in technology, but progress in how we care, coordinate, and continue.

VIII. Conclusion: The Long Now, the Living Future

If we are truly entering an age of longer lives, then longevity is no longer a biological project alone—it is a civilizational one. The challenge ahead is not simply how to extend life, but how to ensure that what we extend is worth living: mentally coherent, socially supported, and morally navigable.

This requires rethinking how we build, lead, and relate. It means investing not just in innovation, but in narrative. Not just in science, but in stewardship. It calls on us to design for the long now: to support projects, institutions, and people that can metabolize change while maintaining a sense of purpose and direction.

I’ve tried in this essay to sketch the outlines of that challenge: mentorship as infrastructure, institutions as living systems, cognitive longevity as an ethical imperative. These aren’t abstract ideals. They are design problems—ones that can be met with creativity, care, and coordination.

To move forward, we must fund and elevate people and programs that make long-term flourishing possible. We must normalize reflection as a skillset, embed mentorship at every level of innovation, and build tools that are not just faster or smarter—but wiser. This isn’t about utopia. It’s about sustainability, dignity, and direction.

The question is no longer just: How long can we live? The real question is: How do we design a future where we want to keep going?

This is the work of our time. Let’s make it count.

See also: https://open.substack.com/pub/cosmosinstitute/p/ai-vs-the-self-directed-career?r=golyz&utm_campaign=comment-list-share-cta&utm_medium=web&comments=true&commentId=116384312